Confessions of a Mathematician

What images do children have of mathematics, mathematicians and what it is to DO mathematics? One way to find out is to ask them! This post provides some suggestions for both young children and those in the upper primary years. It also has some examples of responses from children we have had the privilege to work with in our day to day positions as teachers and educators. They provided rich information about children's perceptions, giving us insight into the learning opportunities and conversations we could design to challenge some of the stereotypes that emerged. There were also some lovely surprises - so read on!

Euclid, The Count, and the little adult

Those of us who were brought up on a rich diet of Sesame Street delighted in The Count and his passion for quantifying just about anything! "ONE, ha, ha, ha, TWO, ha ha ha" - it was joyful and a great way to move from rote counting to 1:1 correspondence.

When we Googled "mathematician" for this post, we didn't get The Count in our first 10 responses. Instead we saw Einstein, Newton, Euclid, Archimedes, Fibonacci, Fermat and Turing.

This is to be expected considering the contributions of these mathematicians and the way they have helped us understand our world.

Interestingly, when we searched "children mathematics", we got stereotypical pictures of children in front of blackboards full of formulas. Quite often these children were depicted with glasses on and conservative clothing - a bit like a little adult.

If these images are the ones most likely to be seen in a simple search, where does that leave room for children and their mathematical identity beyond the famous, the fanciful, and the stereotype?

What is a mathematician?

If we are aiming to discuss and challenge norms about what mathematicians are and what they do, then starting with a child's view of these concepts is helpful.

At some of the schools we have worked at we tried different strategies to derive such perceptions, and used them as authentic data from which to generate goals about our approach to teaching and learning mathematics.

Draw a Mathematician

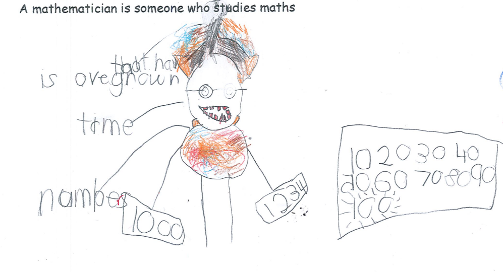

One of these was simply called "Draw a Mathematician". We asked children as young as Year 1 to draw a mathematician. To explicate this a little without swaying the results, we talked about a mathematician as being "someone who studies mathematics".

We analysed these samples, at times asking the students to "tell us" about their drawing so we didn't make too many assumptions about what was represented.

There are many interesting things to notice in these first three colourful representations by 7-year-olds:

-

there is an emphasis on numbers and the operations

-

the equations are written horizontally not vertically

-

two of the 3 have glasses on

-

2 of the 3 are adults - one with a laboratory coat on

-

representations are important - they even become wall posters

-

tools like the rekenrek are used (first pic) at a desk

-

everyone is smiling

The pencil drawings in this section were created by students who are a year older. They seemed to have done some work on labelling!

We can see a greater range of mathematical concepts in these pictures, and the work they have done with the rekenrek has obviously made an impact.

They all have glasses on and there seems to be an association between mathematics and being "smart", having "a big brain" or one that "popped out of head".

Once again, all of these seems to be representations of adults rather than children.

Using these data

This was valuable information for us. These young children seemed to have absorbed societal narratives that presented people who did mathematics as adults who were"the smartest person on earth". They placed these people in classrooms or with no context at all. There were no representations in those we gathered of people, adults or children, studying mathematics in realistic contexts or doing everyday activities. It was good to see that most of people in these drawings were smiling. This may indicate that the children enjoy mathematics, or at least that people who study mathematics like doing it.

We shared the pictures with the children and asked them what they noticed. What did they notice that was the same across the drawings? What did they find interesting?

Taking this information on board, we created some goals in relation to broadening childrens' perceptions of what mathematics was, how it related to our everyday life, and how broadly we could think of "mathematicians".

At the end of the year we repeated the task, comparing the initial drawings to those done at the beginning of the year. One of the drawings at the end of the year can be seen here. It has the child nominating themself as a mathematician, and has Dr Lomas in the picture also. They are the mathematicians.

Confessions of a Mathematician

Draw a Mathematician is an open task can be done at many age levels. It provides rich information about children's perceptions of what a mathematician is.

A strategy to generate more focused information about a child's confidence levels, their ways of working, as well as their perceptions of themselves as mathematicians is the questionnaire we created called Confessions of a Mathematician. If we think of a confession as telling or making something known, we can frame this questionnaire as information that the children are providing to assist us in our teaching and learning of mathematics. We want children to feel safe offering their thoughts and to know how that data will be used.

In this questionnaire, children respond to a number of prompts, either on paper or in an online survey that collates the information. The benefit of using a paper copy is that the initial responses can be reflected on at the end of the year, with the child commenting on any changes that have occurred for them. Using an online version makes it easy to look at whole class, or whole grade responses and discuss what they notice.

The beginning of the questionnaire says: Tell us as much as you can about yourself when you think about maths and doing maths...

The questions that follow are:

-

When you think of maths, what are three things you think of? - three response boxes

-

Who do you think is good at maths (in your class or your year group)? - short answer text

-

What is it that they do that makes them good at maths? - short answer text

-

When you are doing maths in class, how confident are you to solve problems? - 10 point scale: not confident at all to very confident

-

What words describe you as a mathematician? - short answer text

-

Finish this sentence: When I make a mistake in maths... - short answer text

-

What kinds of maths do you enjoy and why do you enjoy them? - long answer text

-

What kinds of maths do you find hard, and why is it hard for you? - long answer text

-

What would you like to do better in maths? - short answer text

-

What help do you need to become better at maths? - short answer text

-

How will you know when you are better at maths? - short answer text

-

Anything else you would like to tell your teacher about yourself when you are doing maths?

You could use less questions but we found this range was just enough to gain the broad picture we were looking for in relation to the students' perceptions, what they found hard and easy, and how we might be able to assist. We used the confidence scale graph as an interesting talking point and made some goals around these data.

When you think of maths, what three things do you think of?

You can see in these data from a class of 8 year olds that a lot of responses relate to operating with numbers, including the names of some of the strategies they know.

Some of the responses are affective: excited, nervous, scared a bit. Others are related to the way the child works during class: hard, with frustration, and not being able to get help.

How confident are you to solve problems in maths?

These data give us an average indication of the confidence levels in this class. This is authentic and purposeful data which we used to generate goals for the coming year. It prompted conversations about confidence in problem solving. It also allowed us to discuss productive struggle and how we manage feelings of confusion.

Further ideas and prompting questions

Other possible prompts you might use individually to generate some ideas from children include:

-

If you had one wish for mathematics learning this year, what would it be?

-

One morning you wake up and you are an outstanding mathematics student. Describe the kinds of things you know and how you feel.

-

List all the ways mathematics can be useful.

We are excited to share these ideas and the possibilities with you. If you use our Confessions of a Mathematician idea, please reference our site so we can give teachers and educators context through this article :)

We have added a Word Document set up already with some of the prompts if you want to get started with the Confessions today!